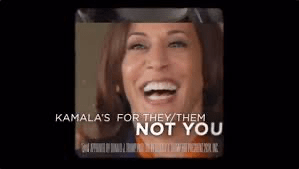

I read in the last week the there was a distinct Democratic downturn that showed up when this political ad (in all its forms) began to be shown. When I looked it up online, they gave the full text as “Kamala’s for They/Them. President Trump’s for You.”

I missed it when it came out because I was mostly hiding from the campaign, so it all feels new to me.

The power in this superbly conceived ad is the meaning of “Them.” All the ad says on the surface is that Kamala is expressing her preference for one way of using personal pronouns over another way. Who would have thought that such a small grammatical preference would carry such a payload.

But, of course, there is more to the ad than the surface meaning. This is aimed at people who have said “him” or “her” to someone and who have been corrected when the person asked to be referred to as “they.” Those people—the people who have been corrected—are the “You” that shows up at the end of the ad.

And like the first part, which seems to be only about a choice of pronouns, this part, which seems also to be only about pronouns, is in fact a powerful statement of advocacy by the Trump campaign. Had the ad said only “President Trump is for You” it would have been feeble and pointless. But this ad points out the alternatives. Kamala is the candidate of the people who look down on you and correct your grammar. Trump thinks your grammar is just fine.

And, in fact, your grammar WAS just fine. Yesterday. But things keep changing and you are supposed to assent to the changes no matter how bizarre they are and to conform to them because you will be “corrected” if you don’t.

And once we change from the correction that is being demanded to the people who are doing the demanding, the range expands very quickly. The same people who find themselves simply unwilling to address another person as “they” are also called racist, sexist, ageist, and whatever other -ists are currently being deplored. And the power of this ad is that it shifts the emotional grievance from the usage to the critics.

Here is how it comes out. Whatever bizarre claims are being made for a new kind of society—different work norms, gender norms, relationship norms, language norms—Kamala is for them and for the people who want all those new things, no matter how ridiculous they might be. And those are the people who look down on you and call you names. So, briefly, they are the “them” of They/Them. Why would you vote for someone who supports Them?

President Trump is against “Them” and he is for “You.” Clearly, “them” is a grammatical usage, but ‘you” refers to real people; people you know. Trump is us. Kamala is them.

So that’s the politics as I see it. That is the stream of public controversy that this usage taps. Down below all that, down among people who are engaged in the gender wars personally and daily, the question is only, “What do I want to be called?” The “they/them” choosers not only reject him and her as inadequate; they also reject the high priority that has always been put on him or her. The people who have been causing them trouble are people for whom: a) him and her are the only two options and b) which one you are determines how you are to be treated.

They/them is a protest against both of those. If I knew and liked someone who preferred to be referred to as “them,” I would make every effort to remember to use the term, despite a lifetime of understanding that it is wrong. But even for this person I liked, it would not take many times of being corrected for me to turn that favor I was doing for my friend into an unwilling obedience to their quirkiness. I would also be turned off by whoever among my friends thinks I ought to be more careful to use the preferred pronoun of the person I had just offended. And I would resent being turned off by people who think I should knuckle under to unreasonable demands.

And when that happens and I see a billboard that says I get to choose between someone who is for They/Them and someone who is for Me, the emotional force is all in one direction. It is Trumpish.

Finally, I, personally, despise Trump and everything Trumpish. I don’t like they/them either. It’s not a “personal preference” if everybody needs to use it. I am blessed with enough verbal fluency that I can manage to stay out of sentences that require me to use or to prominently avoid that pronoun. But I don’t like to have to be that careful all the time.