The last several hundred times I have heard references to a Comfort Zone—except, of course, from the heating and air conditioning people—they have pointed to the virtues of being outside it. Unfortunately, when you have been around and paying attention as long as I have, you hear the same pitches over and over and they get irritating.

I remember the era of “the gray flannel suit” with real clarity. I remember how everyone was urged in the direction of “nonconformity” as if that were a good thing of itself. I remembered those little sermons for quite a ways into the 1960s until it wasn’t fun any more. So these blanket prescriptions are not a new thing for me.

I am used to hearing them at church. I got used to hearing it in the announcements, which are at least partly ad-libbed. Then I heard it several times in the sermons, which are ordinarily read. To me, that means that someone has written it and then, having read it at a later time, has said, “Yes, that is what I want to say.” This last week, I heard it in a liturgical formulation and I said, “Surely not!” So today, I am reflecting.

Some time on the same day I heard this, I heard some NFL announcers assuring each other that a quarterback had just not found a way to get comfortable with the offense in the first half. They didn’t quite say that he had found his “comfort zone” in the second half, when he played very well, but they came close. They said he had “found his rhythm.”

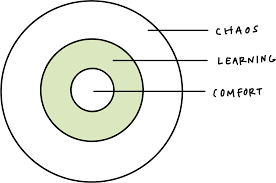

I think I might be like that quarterback. When I can find comfort in a role or a setting, I do my best work. When I can’t, I pay more attention to the setting than I should or more attention to what I am doing than I should, and my performance suffers. That is my experience with my “comfort zone.” [Of more than a hundred images I looked at for “comfort zone,” this is the only one that showed any promise. What advice would I get from these people if I were already in the good green zone? Would they urge me toward the chaos ring because I was showing signs of comfort?]

It is not difficult to lob the “out of your comfort zone” idea at someone else, of course. Anyone who is not taking the risks you think they should take would be vulnerable to such a charge. Or anyone who is more conservative about risks than you are; or someone who values the associated rewards less than you do. I know people who are even more risk averse than I am and I would have no trouble at all in saying to that person, “Why don’t you give it a try? It looks to me as if you would do very well and if not, there are several alternative approaches to try.”

None of that approaches putting a generalized dismissal of comfort zones into the church’s liturgy as if God had something against comfort zones.

I think the complaint against comfort zones has become a linguistic habit, just as the complaint against “conformity” was in the 50s. It isn’t a thoughtful thing to say. It’s just a bromide. Why we should be attributing bromides to God I am not quite sure. [1]

The real loss in the linguistic habit—apart from the dull thoughtlessness of it—is that is doesn’t ask what a comfort zone is for. It doesn’t ask what other questions—not just comfort or no comfort—ought to be asked that are being shouldered aside. It doesn’t ask what benefits we can expect from someone who is operating in the comfort zone. I can see complaining about lack of productivity, of course, but what is the relationship between productivity and comfort?

And even if God is not offended at having “comfort zone” attached to the divinity, maybe it would be offensive enough if God did not want to be represented as a klutz. Well…a Klutz, I guess, being God.

[1] That might not be the use God had in mind when He created bromine. I guess we’ll never know.